- 20+ Years Of History

- 30+ Countries

- 50000 Yearly Production

What Is an Oil Pump?

Ever held a drop of oil on your finger? It's thick, slow, almost lazy. Now imagine pushing that drop through a maze of metal tubes—hundreds of them—inside a running engine. Who does that pushing? The oil pump. Not the flashiest part under the hood, but without it, your car's engine would turn into a scrap heap in minutes. So what is this unsung hero? Let's dive in.

Picture your engine: a chaos of moving parts—pistons slamming up and down, valves clapping open and shut, gears meshing like angry teeth. All that motion creates friction. Friction creates heat. Heat melts metal. Enter oil: the peacemaker. It coats those parts, letting them slide instead of grind. But oil doesn't move on its own. It needs a motivator. That's the pump's job. It's the heart of the engine's lubrication system, pumping life into every crevice.

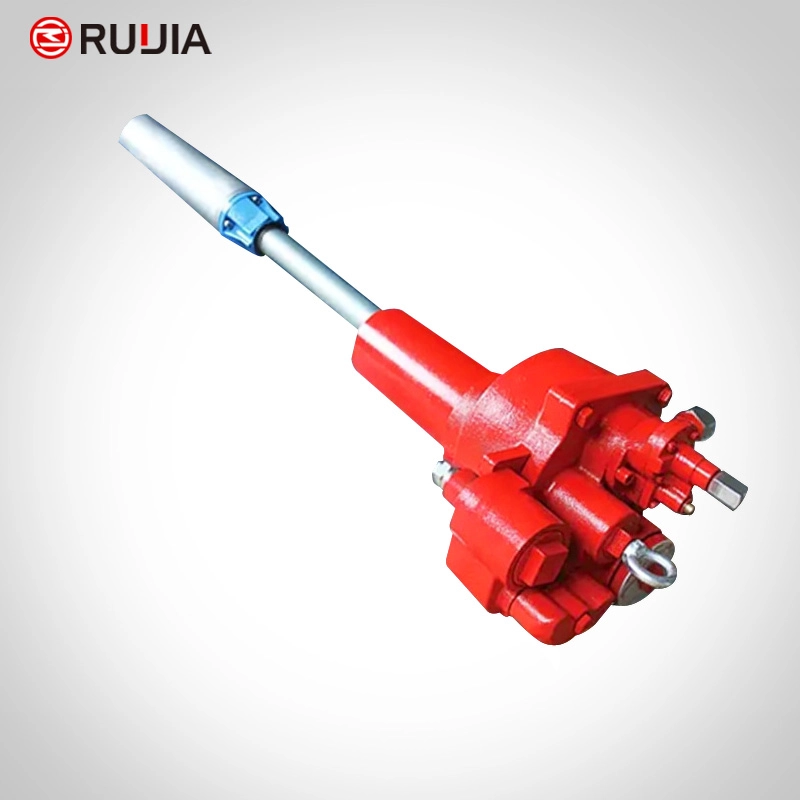

Not all oil pumps are the same. Some sit inside the engine block, submerged in oil like a diver holding its breath. Others mount outside, connected by hoses that snake through the engine bay. Some are driven by the crankshaft, spinning in time with the engine's heartbeat. Others use electric motors, whirring to life the second you turn the key. Different designs, same mission: keep oil moving.

Let's talk about the workhorses: gear pumps. Imagine two gears meshing, teeth locking and unlocking. As they spin, they create a vacuum at the inlet, sucking oil in. Then, as the teeth roll together, they squeeze the oil out the outlet—under pressure. Simple? Yes. Effective? Absolutely. Most car engines use these, their gears churning away, quiet as a whisper. But don't let the simplicity fool you. A single tooth worn down by debris can reduce pressure, turning a reliable pump into a ticking time bomb.

Then there are rotor pumps, the rebels of the oil pump world. They use an inner rotor with lobes that spin inside an outer rotor with groove (notches). As they rotate, the space between them expands and contracts, pulling oil in and pushing it out. Smooth, efficient, and quieter than gear pumps—luxury cars love them. Why? Because they handle high pressures without the gear-driven rumble. Even in silence, they're working overtime.

Ever wondered how much pressure an oil pump generates? About 40 to 60 psi at idle—enough to push oil through tiny passages in the engine block, up to the camshaft, down to the crankshaft, and everywhere in between. Rev the engine, and the pressure rises, matching the increased demand. It's like a firefighter adjusting the hose nozzle: more pressure when the fire's bigger.

What happens if it fails? Disaster. Without oil, metal grinds against metal. Pistons weld themselves to cylinders. Bearings seize. The engine locks up, often with a loud bang that echoes through the car. Mechanics call this a "catastrophic failure"—and it usually means a new engine. That's why oil pumps have relief valves: if pressure gets too high (say, from a clogged filter), the valve opens, letting oil bypass the pump. A safety net, hidden in plain sight.

Oil pumps aren't just for cars. Industrial giants—like the pumps in oil refineries—move millions of gallons daily. These behemoths stand stories tall, their steel bodies vibrating as they push crude oil through pipelines spanning continents. A single one can cost 500,000. Why so pricey? They're built to last 20 years, 24/7, in harsh conditions—deserts, offshore platforms, frozen tundras. Compare that to a car's oil pump, which might cost 200 and last 100,000 miles. Same job, different scales.

Let's get technical, but not dry. The "positive displacement" principle: oil pumps don't just move oil—they displace it. Each rotation moves a fixed volume, no matter the pressure. It's like a syringe: push the plunger, and exactly 10ml comes out, whether you're squirting into air or against resistance. This reliability is why they're used in engines—consistency matters when lives (and engines) depend on it.

Ever heard of a "wet sump" vs. "dry sump" system? In most cars, the oil pan holds the oil, and the pump sits inside it—wet sump. Race cars use dry sump systems: the pump is external, with a separate tank holding oil. It can suck oil from the pan faster, preventing starvation during hard cornering. When a race car takes a sharp turn at 150 mph, oil sloshes to one side. A dry sump pump grabs it before the engine starves. That's why race cars rarely blow engines due to oil issues—their pumps are overachievers.

History lesson: The first oil pumps were hand-cranked, used in steam engines of the 1800s. Mechanics turned a handle, pumping oil to lubricate pistons. By the early 1900s, as cars arrived, pumps became engine-driven—no more cranking. In 1932, GM introduced the first gear-driven oil pump in mass-produced cars, setting a standard still used today. From hand-cranked to computer-monitored—what a journey.

What about the materials? Car oil pumps are often made of cast iron or aluminum. Cast iron is tough, resisting wear, but heavy. Aluminum is lighter, better for fuel efficiency, but less durable. Racing pumps? Sometimes made of billet steel—machined from a single block, stronger than cast parts. It's all about trade-offs: strength vs. weight, cost vs. longevity. Engineers lose sleep over these choices.

Ever noticed that your car's oil pressure light flickers when you start it cold? That's the pump waking up. Cold oil is thick, like molasses, harder to push. The pump struggles at first, then as the oil warms and thins, pressure stabilizes. Modern pumps have variable displacement—they adjust how much oil they move based on temperature. Cold? Move less, but with more force. Warm? Move more, with less effort. Smart, right? It's like a human adjusting their grip—tight for heavy objects, loose for light ones.

Marine oil pumps face a unique enemy: saltwater. Corrosion eats metal, so boat engines use pumps with stainless steel parts, sealed to keep water out. A small leak can spell doom, so they're tested to withstand pressure 50% higher than normal. Boats don't have breakdown lanes—so their pumps can't fail.

Let's talk about the oddballs: vacuum pumps. Some engines (like diesel trucks) use oil-lubricated vacuum pumps to power brakes and emissions systems. They're tiny, tucked under the hood, but critical. A failure here doesn't seize the engine—but it can make the brakes stop working. Scary? You bet. That's why they're built with backup systems, just in case.

What's next for oil pumps? Electric pumps, controlled by computers. They'll adjust pressure in real time, using sensors to monitor engine conditions. No more relying on the crankshaft's speed—these pumps will spin faster or slower as needed, saving fuel. Some might even self-diagnose, sending alerts to your phone when a part wears down. Imagine your car texting: "Oil pump bearing loose—get it fixed in 500 miles." Preventive maintenance, powered by tech.

Let's end with a story. A 1967 Ford Mustang, restored by a mechanic in Iowa. He rebuilt the engine, but skimped on the oil pump—used a cheap aftermarket part instead of OEM. On the first test drive, 10 miles from home, the pump failed. The engine locked up, destroying thousands of dollars in work. The mechanic learned the hard way: the oil pump is the heart—you don't cheap out on hearts.

So, what is an oil pump? It's a lifeline, pushing protection through metal veins. It's a balance of strength and precision, built to work in silence until needed. It's the reason your car starts every morning, your generator runs during a storm, your favorite truck hauls cargo across the country.

Next time you change your oil, take a second to thank the pump. It's been working hard—even if you never thought about it.

Pretty essential, isn't it?